By H.K. Edgerton

As I passed through the Black Historic District in Asheville, a young man would emerge from inside the Black Barbershop, motioning frantically for me to enter. One of the patrons exclaimed, “Well, well, our Black Confederate! Did you get your Christmas Present from South Carolina?” Before I could answer, he went to the next question. “Didn't you come in here ranting at the last Presidential election that when asked about the Confederate Battle Flag, Mitt Romney said that he wouldn't fly the damn thing?”

“And,” he continued, “on December 16, 2011, Nikki Haley, the Governor of South Carolina where the late unpleasantness began, gave her endorsement to the Head Puritan, Mitt Romney. What have you got to say about that?” he asked. Again before I could answer, another patron jumped into the conversation. “Yeah, HK, two or three weeks ago, you came in here so despondent about the Mayor of Lexington [Virginia] whose Great Uncle swore in President Jefferson Davis, orchestrating an Ordinance ban on the Flag in the Shrine City. Looks to us you’re fighting a lost cause.”

And at that very moment, an elderly gentleman whom I didn't know slowly got up from his chair and hobbled over to where I stood. Reaching into his worn pocket purse, he pulled out a folded twenty dollar bill, and where all present could hear, he said to me, “H.K., I hope this can help you go to Columbia with our flag and tell her how we feel. You hang in there.”

I had never felt more proud in my life as everyone present began handing me money from their pockets. What a great day in Dixie!

Showing posts with label On the Confederate Flag. Show all posts

Showing posts with label On the Confederate Flag. Show all posts

Friday, January 6, 2012

Conversations in the Black Barbershop

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

150 Years After It Began, part 2

By Zach Foster

Author of On the Confederate Flag

Continued from Part 1

What have we learned? If anything, Americans have learned that no one wants a second civil war. While Southern nationalism still exists throughout various regions of the country, it is almost exclusively based on philosophy and rhetoric, not on violent revolution. Americans know that politics should never evolve into war. Though our society has learned this lesson, it has succeeded only in applying it at home but not abroad.

While it would be desirable that all Americans (and all people) would treat each other lovingly and work together—even compromise—to solve problems, many have yet to grasp this philosophy. It is encouraging that a shut down of the Federal government was recently avoided through a compromise—albeit a temporary one—between leaders of a Democratic Senate and a Republican House of Representatives. This shows the spirit of cooperation and achievement between factions in a multi-party system. Still, this kind of compromise and the spirit behind it both grow in American politics. Neither side will budge on their aims and nothing gets done. There is still animosity and enmity between political schools of thought.

On the far left of the political spectrum lies a group that has no patriotism or allegiance whatsoever to the country that gave them liberty. This group has only a patriotism for one social class and would seek to destroy the others and ignore the rights (and existence) of the individual for the sake of “society”—for the “greater good.” On the far right lie two groups. One is fiercely patriotic to America but has made it clear that it will not tolerate any religion other than Christianity—contrary to what Christ actually preached in the gospels. The other has no patriotism to this country—only to a particular allegedly superior race—and would seek to destroy all other races for the “greater good.” All of the above mentioned groups present a danger both to American society and all of humanity, for any belief that tolerates nothing but one type of people and one set of beliefs, etched in stone for eternity, is a group whose motives will ultimately lay in overt oppression and genocide.

If there is any legacy of the American Civil War that the author would be proud to one day tell his children or grandchildren about—even if it takes another fifty or one hundred years—it would be that Americans learned to coincide peacefully with each other and with all people as brothers, children of God, and ultimately, human beings with only one world and one future for all to share.

END.

150 Years After It Began

By Zach Foster

Author of On the Confederate Flag

One hundred and fifty years after the Civil War began, the issue still comes up sore in many hearts and even brings emotional pain to the author as he sits and writes this piece, fully conscious of the sobering truth that America is politically divided in a most unhealthy way. Few citizens fully understand and appreciate the magnitude that no war—not even World War II—has killed so many Americans, both soldier and civilian, neither has any war—not even the Vietnam War—so painfully divided public opinion to the point where factions of the same people literally hate each other.

It was on this day, one hundred and fifty years ago in 1861 that the fighting officially began. Seven out of eleven Confederate states had already seceded and this would be the day when the political pissing contest between North and South would erupt into combat. No one on either side died during the bombardment of Fort Sumter, but this day of combat would quickly be followed by skirmishes in Alexandria and elsewhere around the Mason-Dixon line. These skirmishes would be followed by hard combat at Manassas, initiating a trend of battles in which thousands would die at a time and in short amounts of time—a trend only seen again in American history in the two world wars. The fighting has been over since 1865, but the war still lives on in people’s hearts.

What is the legacy of the war? The Union was preserved and continues to live on. Lincoln’s war aims were met, but the legacy does not simply end with the preservation of the Stars and Stripes’ jurisdiction. Yes, the slaves were freed—both Northern and Southern slaves. Still, the Great Emancipation was hampered by government mistakes. The war was won, but greedy or disinterested politicians lost the peace. When Lincoln died, his vision of “malice towards none, charity towards all” died with him. The emancipated slaves who didn’t make it North were ignored by the Federal government and by society. Furthermore, the brutal occupation of the South and the punitive policies inflicted on Southern veterans and government officials—based not on Lincoln’s goals but on the agendas of radicals in Congress—initiated a repression which further crippled the Southern people, as well as draining the Federal coffers. Much of the Southern rural poverty which lasted over a century was caused by the wartime destruction of the means of production and economic self-sufficiency, then aggravated by political repression and military occupation, paired with exploitation by those described as “carpetbaggers.”

After a sleazy backroom deal brought an immediate end to the occupation and Reconstruction, after the carpetbaggers had already made their fortunes and gone home, a repressed and brutalized new ruling class looked to take it out on the only candidates for scapegoating left in the South—the blacks—and inflicted upon them economic and political repression—less-than-second-class citizenship—which was to continue for over a century, contributing also to the disproportionate representation of race in poverty. Does this mean that exclusively Southern whites are to blame for poverty and injustice? No. What it means is that ALL sides and parties directly contributed to the many problems, some of which are still being faced today.

Part 2: What have we learned?

Saturday, December 25, 2010

Zach Foster: On the Confederate Flag, Part 4

A selection from “On the Confederate Flag” 2nd Edition, December 2010

By Zach Foster

This is one in a series of articles being featured on the Political Spectrum as part of Secession Week.

Click to view On the Confederate Flag, Part 3

Let us forgive!

The smoothest way for Americans to forgive secession and the cause of the Civil War, since many Americans still haven’t gotten over it, is to clearly see and accept the opposition’s reasons, whether one agrees with them or not. Political correctness, though it for the most part makes life better for people of different backgrounds, can occasionally do harm. There were mistakes made on both sides of the political struggle preceding the war and Americans need to accept this. It was the South’s mistake for abandoning diplomacy and for abandoning the Union, but it is also the North’s fault for rigidly refusing to appeal to Southern political and economic needs.

Though it was the South’s attempt to form a foreign nation, they were defeated and brought back into the Union . The Civil War has been over for 145 years, yet Americans still feel resentment towards one side or another. When people think of the Civil War, they think of blue and gray, or of slavery and freedom. What many fail to think of is whom a civil war involves—one people, fathers and sons, brothers and friends—killing each other. Most of the military leaders in the Civil War, both Union and Confederate, were old friends and classmates from military school, and the members of the Congress were former colleagues. It is difficult for people to imagine going to war against half of their own high school graduating class. It is doubtful as to whether any American has ever pulled the old High School yearbook from his shelf, opened it up to the pictures and said to himself, Someday there will be a Civil War and I’m going to have to kill him, him, him, and many others because our beliefs differ. This is what happened to America

There is a compelling argument in The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Civil War explaining how Secession was more legal than the American Revolution. Regardless of its argued legitimacy, the Confederate States of America Union . It seems as if some intellectual schools of die-hard Southerners have been sore losers and, even worse, their die-hard Northern counterparts have been sore winners!

It was the revered hero Abraham Lincoln whose vision of reconstruction was “malice toward none; with charity toward all... to bind up the nation's wounds.” Tragically, the South lost its best post-war friend when Lincoln Lincoln Union among the spiteful Southern population. Reconstruction failed to rebuild the Southern infrastructure, failed to educate the emancipated slaves who lacked many skills after a lifetime of servitude (an issue faced today by many North Korean defectors living in the South), and it succeeded only in driving people apart. This failed form of Reconstruction gave rise to the oppressive Jim Crow system.

Americans need to acknowledge that the Civil War is physically over, but that the division still exists today. All Americans need to extend a hand of brotherhood to other Americans whether their ideologies agree or not. Southerners today (with the exception of hate groups and neo-secessionist movements which are few in number) may wave the Confederate flag, but they are loyal to the United States of America

Let their heritage be honored

Unlike other civil wars, the veterans of the losing side of this country’s civil war were not severely punished. Other wars such as the Chinese Civil War saw the losing side driven from the mainland and forced to settle on a small island to avoid violent persecution, with horrid persecution of those left behind. The Vietnam War saw a sloppy evacuation of Saigon by helicopter, followed by ten years of refugees fleeing from imprisonment and execution. This did not happen after the American Civil War, nor was it the objective of either side. The Federal objective in the war was to preserve the Union . This objective was carried out successfully.

Still, there are Southerners who speak out against the “tyranny” of the United States

Some people have tried to move on. The Northern veterans of the Civil War have received the national and historical accreditation that they deserve. Southerners have received only local honors by their descendants until groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans emerged nationally. Just as Southerners need to forgive the United States Armed Forces, the armed forces whom many Southern sons and daughters serve, the rest of the American population needs to forgive and honor the Confederate Veterans who suffered the loss of a war and public scorn similar to that which burdened the Veterans of the Vietnam War. In later decades, Confederate veterans were given pensions by their state of residency. To this pension system, the Federal government did not object or intervene. In all parts of the country, regardless of which side they belonged to, the government acknowledged veterans of the American Civil War.

Moving beyond politics, it’s interesting to note how both flags of the Civil War have moved on from being symbols of war and politics to finding a place as pop-culture symbols. There are many rock and country music groups that have adopted these flags into their album artwork and merchandise. There are also many stores, including Army surplus, where people can easily buy both flags to own or display.

The Confederacy has also established a legacy in history and folklore, with Robert E. Lee arguably becoming the most revered man in Southern history. Several other Confederate leaders have lived on as well. To this day, some of the U.S. Army’s most famous military bases where elite soldiers are trained are named after Confederate generals Braxton Bragg, John Bell Hood, A.P. Hill, and Robert E. Lee. This legacy is acceptable, since a great many other military bases are named for Northern military leaders.

On the appropriateness of flying the Confederate flag

The Confederate flag, though it is a symbol of the history and culture of the American South, is not a political flag—it is a symbolic one. There are only two instances in which it should be appropriate to fly the rebel flag in public places. The first instance is for memorial services for fallen ancestors, or for the graves of Confederate dead. The second instance is for historical context, such as the flag’s use in battle re-enactments, museums, battle sites, or important Southern anniversaries.

Though instances exist in which flying the rebel flag can be appropriate, by no means should the flag fly above Old Glory or any other version of the US United States US

It is appropriate to fly the flag over monuments to Confederate veterans, since they represented their communities and their states which happened to have seceded at the time. It is also highly appropriate to fly the rebel flag on private property in observance of the First Amendment.

Another topic of debate is the appropriateness of the rebel flags flying over the graves of Confederate military dead. This is acceptable and practical, since the rebel soldiers fought and died for that flag. They are entitled to their desired flag over their gravesites. This courtesy is an American military tradition. During World War II, when German prisoners died in stateside captivity or in escape attempts, the US Army would give those POWs proper military burials, including religious benediction and their coffin being draped with the red flag with the swastika. During the Cold War, Soviet soldiers would occasionally die in air or submarine espionage missions. If their bodies were retrieved, they were given their own burial rights, including benediction by Russian Orthodox priests and their coffins being draped with the red Soviet flag with the hammer and sickle. By these standards, the American rebels—our brothers—ought to be allowed their rebel flags at their graves.

For any ceremonial instances that are not historically oriented in which the Confederate flag must be displayed, one format is appropriate. Such a format is to fly the United States US

Moving On

The United States

The Civil War was fought because people abandoned diplomacy and turned prematurely to settling their disputes with weapons. People are guilty on both sides, and only through understanding this can Americans take up the responsibility of binding the country’s wounds and healing. It is our responsibility as Americans, regardless of regional background and pride, to educate ourselves and each other, to understand each other, and to love each other both in the common history and traditions we share and in the wonderful differences which broaden our horizons. “…malice toward none; with charity toward all…”

For further reading

On secession, the Civil War, and Reconstruction

The Civil War: A History, by Harry Hansen, Signet Classics, 2002

Time: Abraham Lincoln-An illustrated history of his life and times, Time Inc. Home Entertainment, 2009

The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Civil War, by H.W. Crocker III, Regnery Press, 2008

On Native American Confederates

p. 101-102 “The Battle

“Native Americans in the Civil War,” NativeAmericans.com,

http://www.nativeamericans.com/CivilWar.htm

Red Fox: Stand Watie and the Confederate Indian Nations During the Civil War Years in Indian Territory, by Wilfred Knight, Arthur H. Clark Publishing, 1987

General Stand Watie’s Confederate Indians, by Frank Cunningham, University of Oklahoma Press

On Black Confederates

Black Southerners in Gray: Essays on Afro-Americans in Confederate Armies, edited by Richard Rollins, Rank and File Publications, 1994

Black Confederates, Edited by Charles Kelly Barrow, J.H. Segars, and R.B. Rosenburg, Pelican Publishing, 2001

Southern Heritage 411, http://www.southernheritage411.com/

On H.K. Edgerton

“A Divisive Flag Makes it to D.C.,” by Brian McKenzie, 2009, http://www.southernheritage411.com/hke.php?nw=301

On Hispanic Confederates

Hispanic Confederates, by John O’Donnell-Rosales, Clearfield Company, 1997

A Life Crossing Borders: Memoirs of a Mexican-American Confederate, by Santiago

About the author

Zach Foster lives with his family in southern California

T-shirst image used courtesy of Matchtingtracksuits.com. Cherokee image used courtesy of inc-art.com. Crossed flags image used courtesy of Sodahead.com. They are included via fair use and the propertyy of their respective owners, not the article author.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Zach Foster: On the Confederate Flag, Part 3

A selection from “On the Confederate Flag” 2nd Edition, December 2010

By Zach Foster

This is one in a series of articles being featured on the Political Spectrum as part of Secession Week.

Click to view On the Confederate Flag, Part 2

The structure of the Confederate Armed Forces

There were several ways in which men could serve in the Confederate Army. Though the Confederate States did have a navy and a Marine Corps, the primary fighting force was the Army. Much like today’s US Army is branched out as the regular Army, the Army Reserve, and the Army National Guard, the Confederate Army was branched into the Army of the Confederate States of America (ACSA), made up of those who had enlisted in the long term, and the Provisional Army of the Confederate States (PACS), made up of short-term enlistments or draftees. The vast majority of men who served in the national army enlisted (or were drafted) into the Provisional Army. Unlike their ACSA counterparts, the PACS soldiers would be discharged once the North surrendered or acknowledged the Confederate States of America

Few blacks made it into the national army, since they were second class citizens in the Confederate States, until black units were authorized in the Army in March of 1865. The majority of blacks who saw combat on behalf of the Confederacy fit into one of three categories: (1) auxiliaries employed by soldiers or the army itself, who armed themselves and more often than not were put in the position to fight or risk capture or death; (2) Home Guard or militia soldiers (there were a great many organized militias with blacks in the beginning of the war, and a great many rag-tag hastily assembled militias toward the end of the war, similar in nature and purpose to the German Volkssturm of late 1944-45, which were often encountered by Sherman’s army during the March to the Sea); (3) civilians that were called up from the locale of a battlefield to provide labor or to fight for a brief period of hours or days (the unorganized militia according to the Constitution). Many Hispanics who served did so in the national army or in the Texas Florida

The Confederate military strength also relied greatly on militias and volunteers. Though the Confederate Army was a new creation, the state militias had existed since the American Revolution, though the nature of the militias varied from state to state. Some were active military entities before the war, training and drilling on a regular part-time basis, while others were inactive militias that were reactivated by their state’s governor and calls were made for volunteer enlistments. Once secession occurred, every state in the Union and the Confederacy activated the state militia.

There were many units of the Confederate military made up from volunteers. These volunteer regiments boosted the strength of either the national army or the state militias, depending on who was issuing the call. Though some state militias occasionally hooked up with the national army to fight in major campaigns, most stayed in their respective state to defend against Union invaders. Most state militia units saw combat, except for those who were formed only on a temporary basis to meet a short-term military goal, as described in the paragraphs above.

Another way that the Confederate armed forces were augmented was through drafting. Towards the end of the war, the Confederate government desperately drafted soldiers of a much wider age range. However, most of the drafting that went on was in the form of temporary impression. Quite often would members of the inactive militia (i.e., any male old enough to carry a gun) be called upon into the state militia or the provisional army to set up defenses around an area in danger of being overrun by the Union, and often they would be charged with working artillery or another vital job that would free up regular soldiers to fight. This is how a great many slaves saw combat, since they rarely had leave to enlist in a regular military entity, but their masters would have no say against the army activating their slave for a short period of time.

Whether a soldier and his respective unit belonged to a local militia, or whether he was in the national army, all confederate military forces waved the Confederate battle flag and earned the right to call themselves Confederate veterans. Men like these, both white and black, were on many occasions given a pension by their state (in the 1880s and 90s) for vital services given to the state during the Civil War.

Why the Confederacy was wrong, but how the Confederate flag is not a threat

Many people see the Confederate flag as a threat to the well-being of the country because of its misuse by radicals and white supremacists such as the Ku Klux Klan. However, if bigots like the KKK and others are the main reason for political correctness to demonize the flag, then Christianity itself ought to be demonized, since the Klan has perverted that as well. The Confederate flag is a symbol, and the meaning of that symbol will lie in the eye of the beholder. Sometimes the beholder will see history, and other times the beholder will see hate.

The Confederate States of America

Thomas Jefferson wrote that when a government becomes tyrannical over a people, those people have the right to overthrow the government. If only such were the case… The Federal government exerted no tyranny whatsoever, nor did the Southern population attempt to overthrow such a “tyrannical” entity. Instead, eleven states seceded from the freest country on Earth in an attempt to run their own program. Though Southerners felt that they were not receiving adequate representation in Congress, they still had two Senators from every state, and numerous U.S. Lincoln

Secession was the great political equivalent of a child, having lost a game of handball, taking his ball from the playground and going home. Secession was the dishonorable abandonment of diplomacy when there were still options on the bargaining table. To have simply broken away from the freest republic on Earth, that to which Southerners had formerly sworn allegiance, was the reason they should be blamed.

Nonetheless, Southerners are not the only ones to blame. Northerners pushed and prodded them all the way in political and economic antagonism. Northern politicians voted to set high tariffs on imported items, damaging the Southern agrarian economy which couldn’t support mass production of goods the way the Northern economy could. Northern politicians allowed themselves to be influenced by abolitionists and, rather than continue to compromise over an economic (though immoral) institution which Southern economy depended on, they set out to end it altogether. Finally, though the Confederate army took Fort Sumter

150 years later, the Confederate flag should not be thought of as a symbol of hate. In 21st century America United States of America Asheville , North Carolina Washington D.C.

Continued in Part 4

Image used courtesy of Confederateamericanpride.com and is used via fair use. It is the property of its respective owner, not the article author.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Zach Foster: On the Confederate Flag, Part 2

This is one in a series of articles being featured on the Political Spectrum as part of Secession Week.

Click to view On the Confederate Flag, Part 1

From “On the Confederate Flag” 2nd Edition, December 2010

By Zach Foster

Political Correctness and the Myth of the White Confederacy

Though a great majority of the soldiers in the Confederate armed forces were Caucasian, by no means should the ethnic minorities who called themselves Southerners be omitted from mention. Historical records and unit rosters show that between 50,000 and 80,000 African-American men fought in gray uniforms. Ironically enough, the first African-American military unit in American history was the First Louisiana Native Guards, formed in 1861 and disbanded in 1862 when Louisiana was re-conquered by the Union (the first United States Colored Troops weren’t formed until January of 1863). Only ten to twenty percent of the black Native Guardsmen switched sides. The overwhelming majority of them remained Confederate patriots. Throughout the course of the war over 10,000 Native Americans and 5,000 Hispanics fought in gray. The latter statistic only includes those who did not pose as white men.

Though slavery existed throughout America—it was simply a fact of life—it would be ludicrous to say that every single black man or Native American or Hispanic was a slave, forced by a white master to fight in his stead. Despite its many shortcomings in social advancement, there was much diversity among the Confederate states, though the Anglo-Celtic culture was dominant. In 1861 two Mexican states offered to secede from Mexico Mexico Florida

Many would wonder why so many Hispanics would fight for the Confederacy if they were often treated as second class citizens? First and foremost, war has historically offered young men the opportunity for adventure and, if they could make heroes of themselves, social advancement. The second and especially powerful reason that many Hispanics were eager to join the rebel army is because they simply had no love for the

Many would wonder why so many Hispanics would fight for the Confederacy if they were often treated as second class citizens? First and foremost, war has historically offered young men the opportunity for adventure and, if they could make heroes of themselves, social advancement. The second and especially powerful reason that many Hispanics were eager to join the rebel army is because they simply had no love for the

Of the estimated one million-man-strong Confederate armed forces, nearly a tenth of the personnel were documented non-whites. This doesn’t include the thousands of fair-skinned soldiers who passed for white. Though they were a minority in the military, at least one third of the Confederate civilian population was African American—slaves mostly—yet the overwhelming, almost complete majority of Confederate voters were white. The requirement for voting was to be a male land owner. By these standards, over ninety percent of white men did not even qualify to vote. A fact often overlooked is that Southern America was a class society. The bottom class consisted of slaves. Above the slaves were the impoverished free people—this class accounted for most Southern whites and nearly all free-people of color (this was the politically correct term of the time) who labored to earn their living. The next class consisted of merchant shopkeepers, or non-wealthy people who were lucky to own some land. The top class consisted of the planters, who owned much land and many slaves.

A minority of non-white plantation owners existed, but few were former slaves. Most had inherited their possessions and status as wealthy descendants of black Frenchmen (Creoles) and Spaniards who had achieved noble status before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, or the descendents of wealthy Hispanics who achieved nobility before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. Any Native Americans who held a high status were most likely born into the elite within their tribes, or were descendants of a union between a Native American and US

Native Americans are a fascinating ethnic group to study in the context of this time period. The vast majority of Native Americans who participated in the Civil War fought for the Confederacy, as well as many nonaligned tribal nations that fought independently against the United States Union in the opening months of the conflict, disassociating himself and trying to disassociate the Cherokee nations with renegade Chief Stand Watie. Oddly enough, the American Civil War broke out in time to engulf a civil war between the Cherokee. Before 1862 came along, Stand Watie was the leader of the majority of Cherokee. Watie was made a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army, leading his people to fight the Union Army and Union tribal warriors in the West. Watie also drafted every able bodied Cherokee male between the ages of seventeen and fifty into Confederate military service. Watie’s forces were among the last to surrender in June of 1865. All Native American Confederates fought especially hard, knowing after well over a century of Ango-Indian wars that they had everything to lose. Native Americans were the group whose grievances against the United States U.S.

There were many other tribes that were caught up in the war, or capitalized on it. The Sioux nation in Minnesota

Many poor Southerners did aspire to own land and slaves, including black and Hispanic citizens, since to own land and slaves was a sign of wealth and social status. Slaves especially were a good commodity to own, since the ownership of slaves was more prestigious than the ownership of land. Any man who owned a slave was well respected, and the various blacks and Hispanics who owned both land and slaves were treated as equals to their white counterparts. Slavery is an immoral institution regardless of what race claims ownership over what other people; but this is just the way life was back then, and the acquisition of human property was tolerated as a sign of prosperity.

It just happened that the majority of slaves were in the South because the need for them to work the land far outweighed the need for their labor in the industrial north. Despite the large abolitionist sentiment in the North, it is often overlooked that many wealthy people owned slaves in the North, and most kept their slaves until the surrender of Confederate forces in 1865. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 freed only the slaves in occupied rebel territory, but not those in the states still loyal to the Union . Northern slaves were freed in 1865, while Southern slaves were freed as Southern territories fell to the Northern Army. Again, slavery was wrong, but it was simply an everyday fact of American life.

Continued in Part 3

The first image is considered to be in the public domain, courtesy of Flickr.com. The second image is used courtesy of Rebelstore.com. The men in the photo are soldiers from the 3rd Texas Cavalry, CSA. They are from left to right: Refugio Benavides, Atanacio Vidaurri, Cristobal Benavides and John Z. Leyendecker. Images are used via fair use and are the property of their respective owners, not the article author.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Zach Foster: On the Confederate Flag, Part 1

A selection from "On the Confederate Flag" 2nd Edition, December 2010.

This is one in a series of articles being featured on the Political Spectrum as part of Secession Week.

On the Confederate Flag

By Zach Foster

The Confederate flag, the republic for which it stood, and the entire war fought over its legitimacy have made up a hotbed of passionate debate for well over a century, and probably will remain so for another fifty years to come. The flag itself is but a symbol, though to many the interpretation and meaning of this symbol varies greatly, with almost as many opinions on it as there are American citizens! Many identify this symbol with racism, oppression, and terrorism, while others identify it as a piece of long-passed history, while a few others identify it with a lost yet noble cause. Feelings and arguments regarding the Confederate flag and the causes for which it has been used are reaching a new fervor on the eve of the 150th anniversary of the Secession.

Despite the varying feelings of love or hate for the Confederate cause, all can agree that the flag unquestioningly symbolizes the darkest period in American history, when the bonds of brotherhood were forsaken as friends and relatives became armed enemies. By no means is this written work an apology or a defense of the Confederate flag, nor is it an accusation or condemnation—it is simply an attempt to provide an accurate and well balanced explanation of the symbol and what it really stood for. It is with much hope that this presentation of facts, opinions, and arguments will bring more clarity to what the flag really stood for, and perhaps more people after reading this will be able to find a little more peace and closure in regards to a long-ago war that somehow manages to still divide Americans.

Identifying the flag

The first step to understanding the Confederate flag is to be able to identify it—there were four flags flown all across the Confederate States of America

There were three Confederate national flags, as the Confederate government changed the flag twice. The first National flag is the Stars and Bars, whose name is mistakenly given to the battle flag. The Stars and Bars was the Southern answer to the Union ’s Stars and Stripes. This flag had three bars, two red and one white, and in the upper-left corner was the blue field with seven white stars, representing the seven states that seceded from the Union in late 1860 and early 1861. The Stars and Bars would be revised to hold six additional stars, four for the final states that seceded at the start of the Civil War, and two for states the Confederacy claimed but didn’t necessarily hold: Kentucky Missouri

The second national flag, Stainless Banner, was significantly different from the Stars and Bars. In the upper-left corner was a miniature representation of the battle flag, and the rest of the flag was white. This new national flag was by no means mistakable for the Union ’s, but was soon altered because to many it looked like a surrender flag, due to seventy-five percent of it being white.

After revision, the third national flag had the same features as its predecessor, but added was a large vertical red bar on the far right, so that it couldn’t be mistaken as a sign of surrender. This was the Bloodstained Banner.

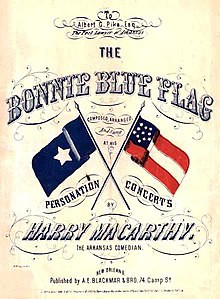

Some may be familiar with the Bonnie Blue Flag, which is a single large white star centered over a dark blue background. This flag was a symbol of Confederate patriotism. It had already served as the official flag for the 1810 Florida Republic Texas Republic

There were also Confederate state flags, as well as many variations of the battle flag and national flags for individual Confederate military units, but those need not be discussed. If any specific Confederate military unit’s flag is being flown by a private citizen, that citizen is most likely a professional re-enactor, a member of a historical society, or a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

What is a Confederacy?

The Confederate government was a special type of government not entirely common in the world. The United States

The Confederate system of government was the opposite. A confederacy is a loose coalition of state governments. In the Confederate States, each state governed itself and answered to no higher form of government. The national government instead answered to the states, and its main purpose for existence was to unite its eleven states as one country with eleven sub-governments, in order to keep the states autonomous without becoming eleven independent countries.

Unlike the United States

Slavery

Nonetheless, it should be noted that the Union may not have dissolved had the representatives from the Northern and Southern states taken a realistic look at the possibilities of ending slavery. Many of the Northern politicians were heavily influenced by the abolitionist special interest while most of the Southern politicians were plantation owners who relied on the institution to provide a labor force. One clamored for the immediate end to slavery while the other wanted to keep it forever.

The Confederate Constitution and most of its state constitutions mentioned the right to maintain slavery, but it must be understood that since the seventeenth century much of the Southern economy was deeply entrenched in slavery and the removal of the institution would have required a phasing out lasting several decades. If slavery were to have been abolished overnight, the plantation-agrarian industry would have taken a massive hit rivaling the recent corporate bankruptcies which required the bailout of hundreds of billions of dollars in order to keep these big corporations from going completely under and causing the loss of countless thousands of jobs, more so than were lost leading up to the bailout.

A much more efficient way to end slavery would have been a phasing out as mentioned above. Over a period of thirty or so years, it may have worked to slowly limit the breeding of slaves, then to limit the sale thereof, then to slowly start freeing slaves and rehiring them as laborers. Hiring plantation workers based on the hourly wage system would have been more economically efficient because:

-As hired laborers, clothing wouldn’t need to be provided, cutting an expense

-Food wouldn’t need to be provided (for free), cutting another expense

-Instead of providing free housing to the workers, workers and their families could live in plantation housing with rent being a fixed deduction from their wages, cutting yet another expense

-Workers absent without leave could be fired or monetarily penalized rather than plantation owners having to organize law enforcement or a posse to go searching for fugitive slaves, saving a great deal of public and private funds, as well as eliminating the need to remove men from the labor force to do searches

-Workers could spend money not used on living expenses on the local economy, thus strengthening the local economy and the free market system

-Business owners, after saving all of the above expenses, could either create jobs or invest in the economy, thus strengthening the local economy and the free market system

The social and moral benefits of a peaceful end to slavery would have far outweighed the economic benefits. First and foremost, all Southern blacks would have been treated as equals by their white counterparts (at least within their social class), rather than just a minority of them. Furthermore, the white/black antagonism of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow era could have been completely avoided and Southern whites and blacks could have lived harmoniously in a fraternal way rather than the paternalistic way of antebellum times.

While the horrors of slavery are often blamed on the South, let it be known that slavery was legal in a number of Northern states, and the vast majority of ships specially built for slave shipping were built and launched from Northern shipyards. Furthermore, tariffs on all imported items, slaves included, were paid to and collected by the federal government. Let it be understood that no one’s hands are clean in regard to the institution of slavery, neither North nor South.

Continued in part 2

First image used courtesy of b36thillinois.org. Second image used courtesy of Wikipedia. Images are used via fair use and are the property of their respective owners, not the article author.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)