A selection from "On the Confederate Flag" 2nd Edition, December 2010.

This is one in a series of articles being featured on the Political Spectrum as part of Secession Week.

On the Confederate Flag

By Zach Foster

The Confederate flag, the republic for which it stood, and the entire war fought over its legitimacy have made up a hotbed of passionate debate for well over a century, and probably will remain so for another fifty years to come. The flag itself is but a symbol, though to many the interpretation and meaning of this symbol varies greatly, with almost as many opinions on it as there are American citizens! Many identify this symbol with racism, oppression, and terrorism, while others identify it as a piece of long-passed history, while a few others identify it with a lost yet noble cause. Feelings and arguments regarding the Confederate flag and the causes for which it has been used are reaching a new fervor on the eve of the 150th anniversary of the Secession.

Despite the varying feelings of love or hate for the Confederate cause, all can agree that the flag unquestioningly symbolizes the darkest period in American history, when the bonds of brotherhood were forsaken as friends and relatives became armed enemies. By no means is this written work an apology or a defense of the Confederate flag, nor is it an accusation or condemnation—it is simply an attempt to provide an accurate and well balanced explanation of the symbol and what it really stood for. It is with much hope that this presentation of facts, opinions, and arguments will bring more clarity to what the flag really stood for, and perhaps more people after reading this will be able to find a little more peace and closure in regards to a long-ago war that somehow manages to still divide Americans.

Identifying the flag

The first step to understanding the Confederate flag is to be able to identify it—there were four flags flown all across the Confederate States of America

There were three Confederate national flags, as the Confederate government changed the flag twice. The first National flag is the Stars and Bars, whose name is mistakenly given to the battle flag. The Stars and Bars was the Southern answer to the Union ’s Stars and Stripes. This flag had three bars, two red and one white, and in the upper-left corner was the blue field with seven white stars, representing the seven states that seceded from the Union in late 1860 and early 1861. The Stars and Bars would be revised to hold six additional stars, four for the final states that seceded at the start of the Civil War, and two for states the Confederacy claimed but didn’t necessarily hold: Kentucky Missouri

The second national flag, Stainless Banner, was significantly different from the Stars and Bars. In the upper-left corner was a miniature representation of the battle flag, and the rest of the flag was white. This new national flag was by no means mistakable for the Union ’s, but was soon altered because to many it looked like a surrender flag, due to seventy-five percent of it being white.

After revision, the third national flag had the same features as its predecessor, but added was a large vertical red bar on the far right, so that it couldn’t be mistaken as a sign of surrender. This was the Bloodstained Banner.

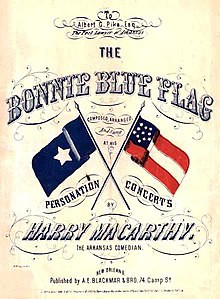

Some may be familiar with the Bonnie Blue Flag, which is a single large white star centered over a dark blue background. This flag was a symbol of Confederate patriotism. It had already served as the official flag for the 1810 Florida Republic Texas Republic

There were also Confederate state flags, as well as many variations of the battle flag and national flags for individual Confederate military units, but those need not be discussed. If any specific Confederate military unit’s flag is being flown by a private citizen, that citizen is most likely a professional re-enactor, a member of a historical society, or a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

What is a Confederacy?

The Confederate government was a special type of government not entirely common in the world. The United States

The Confederate system of government was the opposite. A confederacy is a loose coalition of state governments. In the Confederate States, each state governed itself and answered to no higher form of government. The national government instead answered to the states, and its main purpose for existence was to unite its eleven states as one country with eleven sub-governments, in order to keep the states autonomous without becoming eleven independent countries.

Unlike the United States

Slavery

Nonetheless, it should be noted that the Union may not have dissolved had the representatives from the Northern and Southern states taken a realistic look at the possibilities of ending slavery. Many of the Northern politicians were heavily influenced by the abolitionist special interest while most of the Southern politicians were plantation owners who relied on the institution to provide a labor force. One clamored for the immediate end to slavery while the other wanted to keep it forever.

The Confederate Constitution and most of its state constitutions mentioned the right to maintain slavery, but it must be understood that since the seventeenth century much of the Southern economy was deeply entrenched in slavery and the removal of the institution would have required a phasing out lasting several decades. If slavery were to have been abolished overnight, the plantation-agrarian industry would have taken a massive hit rivaling the recent corporate bankruptcies which required the bailout of hundreds of billions of dollars in order to keep these big corporations from going completely under and causing the loss of countless thousands of jobs, more so than were lost leading up to the bailout.

A much more efficient way to end slavery would have been a phasing out as mentioned above. Over a period of thirty or so years, it may have worked to slowly limit the breeding of slaves, then to limit the sale thereof, then to slowly start freeing slaves and rehiring them as laborers. Hiring plantation workers based on the hourly wage system would have been more economically efficient because:

-As hired laborers, clothing wouldn’t need to be provided, cutting an expense

-Food wouldn’t need to be provided (for free), cutting another expense

-Instead of providing free housing to the workers, workers and their families could live in plantation housing with rent being a fixed deduction from their wages, cutting yet another expense

-Workers absent without leave could be fired or monetarily penalized rather than plantation owners having to organize law enforcement or a posse to go searching for fugitive slaves, saving a great deal of public and private funds, as well as eliminating the need to remove men from the labor force to do searches

-Workers could spend money not used on living expenses on the local economy, thus strengthening the local economy and the free market system

-Business owners, after saving all of the above expenses, could either create jobs or invest in the economy, thus strengthening the local economy and the free market system

The social and moral benefits of a peaceful end to slavery would have far outweighed the economic benefits. First and foremost, all Southern blacks would have been treated as equals by their white counterparts (at least within their social class), rather than just a minority of them. Furthermore, the white/black antagonism of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow era could have been completely avoided and Southern whites and blacks could have lived harmoniously in a fraternal way rather than the paternalistic way of antebellum times.

While the horrors of slavery are often blamed on the South, let it be known that slavery was legal in a number of Northern states, and the vast majority of ships specially built for slave shipping were built and launched from Northern shipyards. Furthermore, tariffs on all imported items, slaves included, were paid to and collected by the federal government. Let it be understood that no one’s hands are clean in regard to the institution of slavery, neither North nor South.

Continued in part 2

First image used courtesy of b36thillinois.org. Second image used courtesy of Wikipedia. Images are used via fair use and are the property of their respective owners, not the article author.

I'd rather be Historically accurate then politically correct...your civil war story sounds like it came out a federal Yankee government history book and we all know those dont tell a shred of truth on the civil war the Lincoln did not care if the slaves were free or not just as long as they do not stay in north..read his diary

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comment, friend. However, what you had to say leads me to believe that you didn't read the other three parts of this 4-part article, which tear apart the anti-Confederate myths and call for the rebel veterans to be honored. This article is actually a defense of the rebel flag, and the introductions which seem to have offended you are specifically constructed to draw in anti-Confederates and place them in an intellectual position to reconsider their beliefs.

ReplyDeleteThe end of each part links directly to the next part. Please take a look at the whole article and I think you'll reconsider my "politically correct" stance (I do attack political correctness later in the article).